Please take a minute to check my books about the Civil War

-

Big Red One, The Civil War€ 4,99

Big Red One, The Civil War€ 4,99

Introduction

The Battle of Shiloh, fought on April 6-7, 1862, was a defining confrontation in the American Civil War, often called “The Death of Innocence.” Located near Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee, the battle was among the bloodiest the United States had ever seen, shocking both the nation and the soldiers themselves. For two days, Union and Confederate forces clashed in a chaotic, brutal conflict that would redefine military tactics, shatter romanticized notions of war, and set the stage for a more ruthless phase of the Civil War. This article delves into Shiloh’s origins, the strategies of key military figures, and the lasting impact of this historic clash.

Origins of the Shiloh Campaign

The origins of the Shiloh campaign trace back to Union leaders’ understanding of the Mississippi River’s strategic importance as a means of dividing the Confederate states. President Lincoln and his generals realized that control over the river would cut off supply lines and hinder the South’s ability to move troops. The “Anaconda Plan,” which envisioned encircling and squeezing the Confederacy into submission, focused on gaining control of the Mississippi as a priority.

For the Confederacy, Kentucky’s neutrality presented both a blessing and a challenge. The state served as a natural buffer between the North and South, but as the Union presence grew, maintaining neutrality became impossible. By late 1861, Union forces began amassing near the borders, with Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston charged with defending Kentucky and northern Tennessee. Union forces steadily gained ground in Kentucky, and Johnston knew he would need to consolidate his forces if he hoped to retain control.

Early Confederate Moves in Kentucky and Tennessee

Confederate movements into Kentucky marked a turning point in the war’s western theater. In autumn 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk moved into Kentucky, anticipating Union General Ulysses S. Grant’s plan to push through to the Mississippi. This maneuver, intended to prevent the Union from gaining a foothold, actually escalated the conflict as Union forces mobilized in response. Grant quickly occupied Paducah, strategically located at the mouth of the Tennessee River, securing a valuable staging ground for further advances.

This back-and-forth across Kentucky ultimately forced Johnston to focus on protecting Tennessee. Kentucky’s unstable neutrality broke, with Confederate forces finding themselves consistently on the defensive against the larger, better-supplied Union troops. Johnston’s decision to move his forces toward Tennessee became a calculated gamble: by ceding some ground, he could hopefully concentrate his forces where they were most needed. However, this decision left Confederate defenses stretched and vulnerable, setting the stage for the battle at Shiloh.

The Convergence on Shiloh

Grant’s campaign targeted the strategically vital railroad junction at Corinth, Mississippi, which connected the Confederacy’s western and eastern theaters. Union forces prepared for an ambitious push southward, while Confederate leaders, including Johnston and his second-in-command, General Beauregard, devised a risky plan to strike first. Realizing they could not match Union forces in numbers or resources, Johnston and Beauregard planned to converge multiple Confederate units at Shiloh, aiming to surprise the Union before their reinforcements from General Buell’s Army of the Ohio could arrive.

The challenge lay in coordinating the diverse Confederate forces quickly enough to launch a unified attack. Johnston and Beauregard assembled troops from as far as Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, marshaling all available forces for a decisive encounter. However, the Confederate advance was hampered by logistical challenges, including muddy roads and heavy rain, which delayed their march and nearly derailed their plans. Despite these setbacks, the Confederate command pressed on, eager to secure a victory that would protect Corinth and the Mississippi Valley from Union control.

Union Preparations and Assumptions at Pittsburg Landing

The Union encampment at Pittsburg Landing was established along the banks of the Tennessee River, providing easy access to supplies but leaving forces vulnerable on three sides. Grant’s forces, numbering about 40,000, had camped at Pittsburg Landing for nearly a month as they awaited reinforcements under Major-General Don Carlos Buell. While they had encountered Confederate scouts and skirmishers, Union commanders, including Sherman, dismissed reports of an imminent attack, focusing instead on training and drilling their inexperienced troops.

Union forces did not establish a formal defensive line, instead positioning their divisions for convenience near access points to water and firewood rather than strategic defense. Sherman, in particular, ignored warnings from officers like Colonel Peabody, who reported increased Confederate activity in the surrounding areas. The Union’s unpreparedness would soon lead to one of the most chaotic opening encounters in Civil War history.

Confederate Forces Assemble

Confederate forces endured a grueling march from Corinth to Shiloh, facing severe logistical challenges. Heavy rains and mud made roads nearly impassable, delaying the advance by days. Soldiers suffered from hunger, fatigue, and exposure, with over 7,000 men too ill to continue and left behind at Corinth. Despite these difficulties, the Confederate high command was determined to launch an offensive against the Union forces camped at Pittsburg Landing.

Under Johnston’s direction, Confederate troops lined up in three main corps, with Hardee’s Corps positioned at the front to lead the attack, followed by Bragg’s and Polk’s Corps. Johnston hoped to surprise the Union forces, taking advantage of their vulnerable encampment and the natural barriers of the Tennessee River behind them. Despite the challenges, Johnston’s troops were primed for battle, with many believing that victory at Shiloh could change the course of the war in the western theater.

The Eve of Battle – Confederate Plans and Union Unawareness

By the night of April 5, Confederate forces had reached the outskirts of Pittsburg Landing, taking positions around the Union camp. Johnston and Beauregard intended to strike at dawn, but coordination issues and exhaustion from the long march led to further delays. Though the plan relied on speed and surprise, Beauregard urged caution, fearing the Union was already aware of their presence. However, Johnston overruled Beauregard, determined to press forward with the attack.

Meanwhile, Union forces were unaware of the full Confederate presence. Despite numerous signs and reports, the Union command remained unconcerned. Picket lines reported scattered encounters with Confederate scouts, but most officers attributed these incidents to small skirmishes rather than a full-scale attack. As dawn approached on April 6, Confederate forces stood ready to launch a surprise assault, while Union soldiers slept, entirely unprepared for the fight ahead.

The Battle Begins: Outpost Skirmishes and Initial Engagements

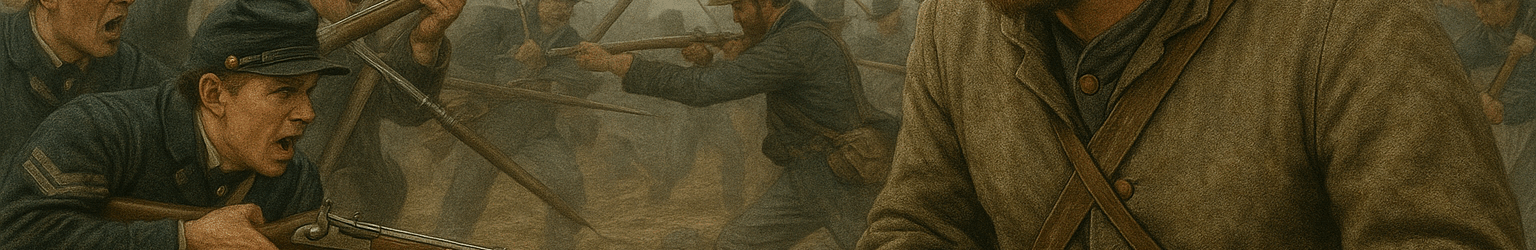

The battle began before dawn as Confederate forces advanced, colliding with Union pickets in Fraley Field. Colonel Peabody of the Union army had sensed Confederate forces moving in and sent a reconnaissance patrol, which met Confederate skirmishers head-on. The skirmish quickly escalated, and Confederate soldiers pressed forward, catching many Union soldiers completely unprepared and still in their tents. Union forces struggled to form defensive lines amid the confusion, with some soldiers forced to grab weapons and ammunition on the run.

The Union’s lack of preparedness became clear as Confederate troops broke through the initial outposts, pushing deep into the Union camp. Union leaders scrambled to organize a defense, but the initial Confederate assault was swift and relentless, overwhelming multiple Union regiments and sowing panic among the troops. As the Confederates surged forward, the Union soldiers realized they were facing a far larger and more organized enemy force than anticipated.

The First Assault – Confederate Charges and Union Resistance

The opening Confederate assault, led by Hardee’s Corps, struck the Union divisions with devastating force. Confederate soldiers advanced in waves, engaging Union troops still struggling to establish defensive lines. Sherman’s division bore the brunt of the early attacks, with Confederate troops overwhelming Union positions and forcing Sherman’s men into a chaotic retreat. By mid-morning, the Confederate momentum had pushed Union forces back, capturing large portions of the Union encampment.

Despite the initial chaos, Union forces began to rally, with Grant and Sherman working to stabilize their lines. As Confederate forces pressed on, Union soldiers regrouped in pockets, mounting fierce resistance and slowing Confederate progress. The relentless Confederate assault, however, showed no sign of slowing, and Union forces suffered heavy casualties as they were pushed toward the river.

Union Resilience and Strategic Withdrawals

As Confederate forces advanced, Grant focused on organizing a series of defensive positions, making use of the wooded terrain and natural barriers around Pittsburg Landing. By establishing successive lines of defense, Grant and his commanders managed to create a layered defense that absorbed much of the Confederate assault’s momentum. Union troops, initially caught off-guard, began to regroup and counterattack, preventing the Confederate forces from achieving a quick victory.

Strategic withdrawals and the commitment of reinforcements helped Union forces buy time and space. As Confederate troops encountered stiffer resistance, the intensity of the fighting increased, with close-quarters combat and high casualties on both sides. This resilience allowed the Union to hold out long enough for reinforcements to arrive, marking a critical turning point in the battle.

Key Figures in the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh featured numerous key military leaders whose decisions shaped the course of the conflict. On the Union side, General Ulysses S. Grant demonstrated his characteristic resilience, refusing to give up the field despite initial setbacks. General William T. Sherman, known for his later campaigns, fought tenaciously to hold his ground, suffering multiple wounds but continuing to lead his troops.

Confederate commanders, including General Albert Sidney Johnston and General P.G.T. Beauregard, faced enormous pressure to deliver a decisive blow. Johnston’s leadership was marked by his presence on the front lines, a decision that ultimately led to his fatal wounding. Beauregard, who assumed command after Johnston’s death, continued to push forward but faced increasing difficulties as the battle wore on. Each leader’s unique approach contributed to the bloody, chaotic nature of Shiloh.

The Death of General Albert Sidney Johnston

One of the most significant moments of the battle occurred with the death of General Johnston, the highest-ranking Confederate officer on the field. Johnston led from the front, rallying troops and directing attacks personally. In the heat of battle, Johnston was struck by a bullet, sustaining a wound to his leg that severed an artery. Unaware of the severity of his injury, Johnston continued to lead until he collapsed from blood loss. His death left a void in Confederate leadership and had a demoralizing effect on the troops.

Beauregard took command, but the momentum of the Confederate assault slowed as news of Johnston’s death spread. His loss was a critical blow to Confederate morale and disrupted the cohesion of the attack, ultimately affecting the Confederate strategy for the remainder of the battle.

The Turning Point – Hornet’s Nest and Union Counterattacks

A defining engagement in the Battle of Shiloh took place at the “Hornet’s Nest,” where Union soldiers under the command of Generals Prentiss and W.H.L. Wallace held out against repeated Confederate assaults. Positioned in a sunken road surrounded by dense thickets, Union forces managed to repel wave after wave of Confederate attacks, buying precious time for reinforcements to arrive. The Hornet’s Nest became a symbol of Union determination, with Prentiss and his men ultimately choosing to surrender rather than abandon their position.

The fierce resistance at the Hornet’s Nest slowed the Confederate advance, forcing Confederate forces to divert resources and attention. This delay allowed Union reinforcements from Buell’s Army to arrive, shifting the balance of the battle and turning the tide in favor of the Union.

The Arrival of Reinforcements and the End of Day One

As night fell on April 6, Union forces received a crucial boost with the arrival of reinforcements from Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Confederate forces, exhausted and disorganized after a day of relentless combat, struggled to regroup for another assault. Grant, now reinforced, began preparing a counteroffensive for the following day. The Union’s ability to hold on and receive reinforcements turned what could have been a disastrous loss into a hopeful second chance.

Confederate leaders were forced to reconsider their strategy as their troops faced exhaustion and dwindling supplies. Beauregard, now in full command, knew that the following day would be decisive but faced an uphill battle as Union forces consolidated and prepared to launch a counterattack.

The Second Day of Battle – Union Counteroffensive

On April 7, reinforced Union forces launched a counteroffensive against the weakened Confederate lines. Buell’s fresh troops joined Grant’s remaining divisions, overwhelming Confederate forces and pushing them back toward Corinth. Despite attempts by Confederate leaders to hold their ground, exhaustion and casualties had taken a toll, and the Confederate lines eventually collapsed.

Beauregard ordered a retreat, marking the end of the Battle of Shiloh. While the Union’s counteroffensive proved successful, both sides had suffered immensely, with the battle resulting in nearly 24,000 combined casualties. Shiloh underscored the brutality of the Civil War and foreshadowed the even bloodier confrontations yet to come.

The Aftermath of Shiloh and its Impact on the Civil War

The aftermath of Shiloh sent shockwaves across the nation. The staggering casualty counts and stories of chaotic, brutal fighting shocked civilians and military leaders alike. Shiloh dispelled any remaining illusions about a quick, decisive end to the Civil War, revealing the grim reality of large-scale warfare. Union leaders were forced to rethink their strategies, while Confederate forces saw the loss as a warning of the Union’s growing strength.

The “Death of Innocence” at Shiloh changed the nature of the war, with both sides adopting more systematic approaches to combat, including better training and more strategic defenses. The battle’s legacy lives on, serving as a testament to the war’s brutal toll and the sacrifices made by soldiers on both side