The Battle of San Juan Hill, fought on July 1, 1898, was the climactic land engagement of the Spanish–American War and one of the most defining moments in the emergence of the United States as a major military and imperial power. Taking place on the island of Cuba, then a Spanish colony, this campaign was part of a larger American operation aimed at ending Spanish colonial rule in the Caribbean and asserting U.S. influence in global affairs.

Strategic Context

By mid-1898, the war had already seen naval victories in Manila Bay and the blockade of Santiago de Cuba. The American high command, recognizing that Spanish forces in Santiago could only be decisively defeated by land, launched an ambitious amphibious invasion. After disembarking at Daiquirí and Siboney, U.S. troops began a difficult overland march through jungle terrain toward Santiago.

The Spanish defenders had established strong fortifications on two key elevations, San Juan Hill and the smaller Kettle Hill, positions that protected the eastern approach to the city. These hills were covered with barbed wire, protected by trenches and blockhouses, and occupied by Spanish regulars equipped with Mauser bolt-action rifles and artillery. The Americans would be advancing across open ground in punishing tropical heat, under fire.

The Battle Unfolds

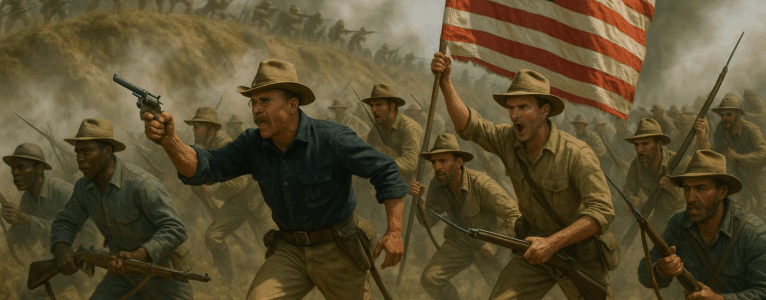

The assault on the heights involved multiple U.S. Army units, including elements of the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, better known as The Rough Riders, and seasoned Black regiments known as the Buffalo Soldiers (notably the 9th and 10th Cavalry, and the 24th and 25th Infantry). These African American troops, often overlooked in popular accounts, played a crucial role in the success of the assault, bearing the brunt of the initial push and providing critical fire support.

On July 1st, American forces first engaged in a bloody encounter at El Caney, a diversionary attack that proved far more difficult than anticipated. The main action, however, came in the afternoon, when troops advanced up the ridges under relentless enemy fire. There was no artillery support to soften the enemy positions, much of the attack was carried out in disorganized rushes and bayonet charges.

Theodore Roosevelt, who had resigned as Assistant Secretary of the Navy to join the fight, led his dismounted Rough Riders in a bold, now-legendary charge up Kettle Hill. Accounts differ on whether he led from the front or followed a general advance, but Roosevelt’s courage, mounted briefly on horseback before charging on foot, became an enduring image of American valor.

Meanwhile, General Jacob Kent’s division tackled San Juan Hill itself, suffering heavy casualties but ultimately capturing the position after savage, close-quarters fighting.

The Aftermath

By sunset, both San Juan and Kettle Hills were in American hands. Spanish forces had retreated into Santiago, demoralized and encircled. Though the Battle of San Juan Hill lasted only a single day, it was incredibly costly, over 1,200 American casualties, many due to heat stroke and tropical disease, and an estimated 600 Spanish casualties.

But the psychological impact was enormous. Within two weeks, Santiago surrendered. The U.S. victory broke the back of Spanish resistance in Cuba and led to the end of the war with the Treaty of Paris in December 1898.

The Larger Significance

The capture of San Juan Hill was more than just a tactical victory, it signaled the arrival of the United States as a global military force. For the first time, American soldiers had fought and won a major overseas campaign. The aftermath of the war saw the U.S. annex Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, signaling the birth of an American empire. It also led to the establishment of a naval base at Guantánamo Bay, which remains in U.S. hands to this day.

Roosevelt, who emerged from the war a national hero, would ride the fame of San Juan Hill to the vice presidency in 1900, and to the presidency in 1901 following McKinley’s assassination.

But the battle also cast a long shadow. The war and its consequences marked a new era of American interventionism. The conflict in the Philippines soon escalated into a brutal insurgency. Questions arose about race, empire, and morality, issues that would continue to haunt American foreign policy in the 20th century.

Conclusion

The San Juan Hill campaign exemplifies a moment of heroism, transformation, and contradiction. It was a day of bold charges, selfless sacrifice, and vivid personalities. It was also a day that revealed the costs of empire and the unpredictability of military glory. In one afternoon, the United States proved itself not only capable of projecting power but also willing to bear the burdens, and consequences, that came with it.

The guns on that hill fell silent long ago, but the echoes still shape the contours of Ameri