When the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion lifted off from English airfields on the night of November 7–8, 1942, they were about to make history, and nearly disaster. It was the first American airborne combat operation of World War II, part of Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of French North Africa.

What was meant to be a precision strike turned into one of the most scattered and confused jumps in airborne history. The paratroopers were brave, their equipment new, their commanders ambitious, but the weather, navigation, and planning were all against them.

The Mission: Seize the Airfields Before Dawn

The 509th PIB, under Lieutenant Colonel Edson D. Raff, was tasked with jumping into Algeria to capture two vital airfields near Oran, La Sénia and Tafaraoui. Control of those airstrips would allow Allied fighter and transport aircraft to operate inland immediately after the landings.

It was a bold plan. The men would take off from RAF St. Eval and Lands End in Cornwall, fly more than 1,500 miles, refuel in Gibraltar, and then cross the Mediterranean Sea at night to reach their drop zones near Oran by dawn.

This was uncharted territory, literally. No U.S. paratroopers had ever flown such a long combat route. The C-47 pilots were mostly inexperienced with night navigation over open water. The crews had no radar, no homing beacons, and unreliable maps. The jump zones were identified only from reconnaissance photos and vague landmarks.

On paper, it was a daring stroke of airborne innovation. In the air, it became an exercise in survival.

A Long and Miserable Flight

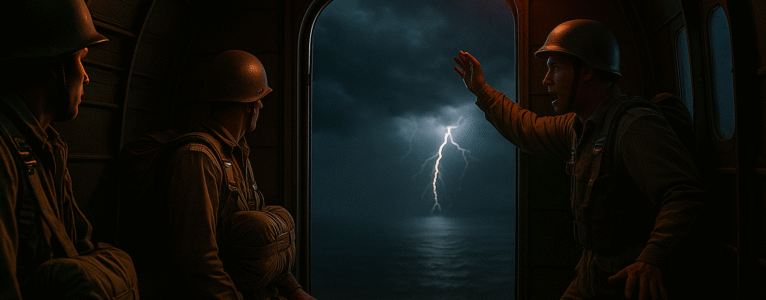

The paratroopers climbed aboard their C-47s late on November 7, weighed down with full field packs, parachutes, reserve chutes, and weapons. Each aircraft carried about 15–18 men, with one or two officers per stick. The men were cold, tense, and exhausted even before takeoff.

The flight south was long and punishing. Winds buffeted the aircraft, and the weather quickly deteriorated. The planned refueling stop in Gibraltar became a congested nightmare as dozens of aircraft circled the tiny airstrip in darkness. Some planes never even found it and had to turn back to England.

hose that made it refueled under blackout conditions and took off again for the final leg, the stretch across the Mediterranean Sea. That’s where things truly fell apart.

The weather over the Med was atrocious. Heavy rain and thunderstorms built up along the route, and the primitive navigation systems of 1942 were no match for it. Many aircraft were blown miles off course. Some flew too far east toward Tunisia, others drifted west toward Morocco. A few crews became so disoriented they thought they were over the sea when they were already inland, or vice versa.

The formation that left Gibraltar as an organized stream of aircraft quickly dissolved into isolated blips fighting through wind and cloud.

Scattered to the Winds

When the order to jump finally came near dawn on November 8, few pilots were anywhere near the intended drop zones.

Some sticks jumped close to La Sénia Airfield, roughly on target. Others dropped miles away in barren countryside. One C-47 released its paratroopers over Spanish Morocco, more than 300 miles off course. Another group landed near Sicily, believing they were still over North Africa.

The results were so chaotic that of the 39 planes that left England, only about 10 managed to drop paratroopers near the correct area. The rest were scattered across an area the size of Western Europe.

Communication was almost impossible. The airborne radios either malfunctioned or were damaged during the jump. Ground troops expected the paratroopers to appear at certain hours, but they never came. Meanwhile, Vichy French defenders at the airfields had no idea who was landing, friend or foe, and opened fire at anything that moved.

It was, in every sense, a debacle.

Improvisation and Courage on the Ground

And yet, the 509th made something out of the wreckage. Small groups of paratroopers, sometimes as few as a dozen men, regrouped wherever they could and began acting independently.

Some captured crossroads and fuel depots. Others cut telephone lines, harassed Vichy French patrols, and spread confusion behind enemy lines. One particularly determined group managed to capture an entire French garrison, convincing the defenders they were part of a much larger force.

By the time Allied armored columns reached Oran later on November 8, a few exhausted paratroopers from the 509th were already holding key points on the approaches to the city.

Their actions didn’t unfold according to plan, but they helped disrupt communications and morale among the defenders, smoothing the way for the amphibious landings.

Lessons Learned: The Price of Inexperience

The airborne operation during Operation Torch was officially considered a partial failure. The drop zones were missed, coordination broke down, and navigation errors scattered the force. But those costly mistakes became the foundation for the Allied airborne doctrine that followed.

After North Africa, planners realized the need for:

- Improved weather forecasting and alternate drop plans.

- Dedicated pathfinder units to mark DZs with lights and radio beacons.

- Better training for C-47 pilots in formation flying and navigation under combat conditions.

- Tighter coordination between airborne and ground forces, especially when operating across multiple time zones and weather systems.

By the time of the next major jump, Sicily in July 1943, those lessons had begun to take hold (though even that operation suffered from friendly fire and scattering).

The North Africa experience taught the paratroopers a brutal truth: it wasn’t the jump that was hardest, it was everything that came before and after.

Legacy of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion

Despite the disastrous start, the 509th went on to earn a legendary combat record. They fought through Tunisia, dropped again in Salerno and Anzio, and later joined the campaigns in Southern France and the Battle of the Bulge.

Their first combat jump in North Africa remains a symbol of raw determination and courage, proof that even when everything goes wrong, the airborne spirit doesn’t break.

Today, military historians view the 509th’s 1942 jump not as a failure but as a necessary experiment that paved the way for the airborne successes of D-Day and beyond. The battalion’s motto, All the Way!, captures exactly what that first generation of paratroopers proved: they’d go anywhere, through any storm, for the mission.