In the autumn of 1944, with the fields of France behind them and the Rhine still far ahead, American soldiers stood at the edge of something they’d never faced before: the German homeland.

For months, they had fought through hedgerows, farmlands, and ruined villages, liberating territory from Nazi occupation. But Aachen wasn’t occupied territory. It wasn’t France. It wasn’t Belgium. Aachen was Germany. Real, ancestral, blood-and-soil Germany. A city whose foundations were laid by Charlemagne, the so-called “Father of Europe,” and whose identity had been carefully mythologized by Hitler’s Reich as a holy cornerstone of the Aryan empire.

Now, it was in the crosshairs.

The orders were simple on paper: take Aachen. In reality, it was a brutal, chaotic, and punishing urban siege that marked the beginning of a new, bloodier chapter in the war, fighting the Germans on their own soil.

The Road to Aachen

By September, Allied forces had reached the borders of the Reich faster than anyone expected. After the breakout from Normandy and the liberation of Paris, American troops pressed hard through Belgium and Luxembourg. But momentum slowed as they neared the Westwall, known to the Allies as the Siegfried Line. This was no minor obstacle. It was a sprawling network of bunkers, pillboxes, minefields, and tank traps designed to bleed any invader dry.

Just beyond that line lay Aachen. Strategically, it could have been bypassed. But politically and symbolically, it was irresistible. Eisenhower knew what it would mean to take the first German city. So did Hitler, who declared Aachen a “fortress city” and ordered it defended to the last man.

The job fell to the U.S. First Army under General Courtney Hodges. The plan was to surround the city, isolate it, and force its surrender. But by the time the first riflemen reached the outskirts, it was already clear: this would be no bloodless siege.

The Encirclement

In early October, the noose began to tighten. From the north, the 30th Infantry Division clawed through the ruins of small towns and fortified ridgelines. Every farmhouse was a bunker. Every forest trail, a death trap of mines and machine-gun fire. Meanwhile, the 1st Infantry Division, The Big Red One, advanced from the south, slogging through dense woods and concrete pillboxes that seemed to regenerate as fast as they were destroyed.

The fighting was slow, cruel, and personal. Flamethrowers and satchel charges became standard tools. Tank destroyers were brought forward to blast open reinforced doors. American GIs learned quickly that a house could be cleared one day and reoccupied by nightfall. German Volksgrenadiers and remnants of SS units fought with a tenacity born not just of discipline, but desperation. For them, this wasn’t France or Poland. This was their soil.

By mid-October, the Americans had sealed off the city completely. But the defenders weren’t surrendering.

Urban Hell

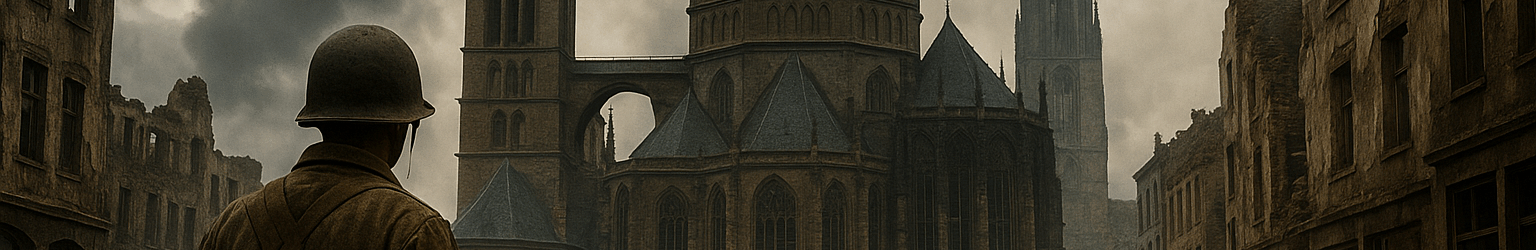

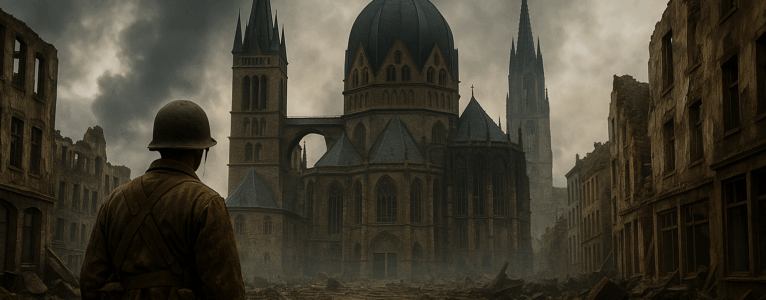

On October 13, the 1st Division was ordered into Aachen itself. What followed was not a battle in the conventional sense, it was a crawl through hell.

Street by street, house by house, floor by floor, U.S. infantrymen fought their way into the city. German snipers picked them off from church towers and attic windows. Panzerfaust teams lurked in basements, waiting for the echo of tank treads before letting fly with armor-piercing rockets. American engineers were forced to blast open doorways and collapse stairwells just to keep the enemy from returning the next day.

The city itself became unrecognizable. Rubble clogged the streets. Fires raged out of control. Artillery thundered day and night, turning centuries-old cathedrals and apartments into heaps of broken stone.

Inside the ranks, exhaustion set in fast. Squads that had started with twelve men were down to six or five. Medics worked triage in ruined wine cellars. Meals were eaten cold, if at all. Soldiers slept in shifts, if they slept at all. There were no front lines, just walls, corners, and the occasional whisper of movement behind them.

Still, they pressed on.

The Final Stand

By October 18, the defenders of Aachen were cornered in the city center. Their commanding officer, Colonel Gerhard Wilck, knew he was beaten. His supply lines were cut, ammunition was nearly gone, and his men were either dead or starving. But he had his orders: hold the city.

Still, even fanaticism has a breaking point.

On October 21, Wilck surrendered. What remained of his garrison, about 3,000 men, emerged from the ruins. They looked more like ghosts than soldiers. The American flag was raised over the blasted remnants of Aachen’s town hall. For the first time in the war, a German city had fallen to the Allies.

There was no celebration.

The cost had been staggering. Over 5,000 American casualties. Entire platoons wiped out. Buildings reduced to powder. And yet, Aachen was just one city. One fortress. The gateway to the Reich was open, but what lay beyond was even worse.

Legacy of a Ruined City

The capture of Aachen marked a turning point, not just militarily, but psychologically. It proved that the German Army, while wounded, would fight tooth and nail for every block of its homeland. It showed that Hitler’s fortresses were not invincible, but neither would they fall easily. And it reminded everyone, from generals to grunts, that the road to Berlin was going to be long and drenched in blood.

For the men who fought there, Aachen would forever be a name carved in fire.

You didn’t take a street in Aachen. You destroyed it, then crawled over the rubble looking for what was left.